Tajbibi Abualy Aziz (1926-2019) Part One

Essay

TAJBIBI ABUALY AZIZ

(1926–2019)

Part One

A Satpanthi SitaPreamble

TAJBIBI ABUALY AZIZ, my beloved mother, passed away on July 26, 2019. I present here a memorialization of her life in three parts, the first of which is presented below. The second and third parts (see the right sidebar) will be published in future issues of the Review.

Part One presents a photo essay of her life bookended by a Prologue and an Epilogue. The Prologue sets the frame of the essay by posing the question whether the kind of Satpanth faith that my mother grew up in and lived possesses any lessons or relevance for the young Ismaili women of the Jamats in Euro-American societies.1I prefer to use the term “Euro-American” in place of the conventional “Western” to reflect its civilizational, as opposed to its geographical connotation. Australia and New Zealand are not “Western” geographically—Queensland and New South Wales are located east of Japan—but they are appropriately “European” in their civilization. The Prologue is followed by the Photo Essay, which in turn is followed by the Epilogue. In the Epilogue I return to the question that I posed in the Prologue and offer some conclusions from my mother's life that the young women—especially college-educated young women—in the Euro-American Jamats may wish to reflect upon.

Part Two will focus on my mother's 20-year teaching experience at the Aga Khan schools in Dar es Salaam. Her teaching experience offers important, relevant and, in my view, very timely lessons for the Jamat's program for the training of religious education (RE) teachers.

Part Three will present a historically informed disquisition on the nature of the Satpanth Ismaili faith that my mother grew up in and lived to the end. It will identify distinctive features of this Satpanth faith that were at the core of her own faith and that also offer an instructive contrast with the other historical Ismaili traditions. These distinctive features of Satpanth—for example, the Ginans' relatively strong feminine character and the distinction between patriarchy and androcentrism that this “feminism” clarifies—present spiritual, intellectual and moral questions to our Jamat concerning the place and role of these features in the emerging Quranocentric conceptualization and practice of the Ismaili Tariqah.2In a future essay I will draw out and explain the distinction between the Ismaili Tariqah and the several Ismaili historical traditions.

Prologue

YOUNG ISMAILI WOMEN living in Euro-American societies are enjoying levels of achievements and degrees of freedom in all walks of life that were beyond the dreams of their mothers, grandmothers and great grandmothers.

They are highly educated and increasingly count among their ranks doctorates and international-caliber academics. They have built successful careers in academia, business and the professions; they have risen to senior executive and management positions in corporations and government; and they are now confidently seeking political careers to represent and serve fellow citizens in public office.

In their lifestyle, too, young Ismaili women enjoy freedoms that their mothers and grandmothers could not imagine. They are able to choose their partners, modes of relationship—including same-sex relationships—and sexual orientation (including transgender identity). They are free to live independently and, among other freedoms, to develop their own understanding and practice of the Ismaili Tariqah.

These unprecedented freedoms, and the achievements that these freedoms have brought them, are the fruits of the unrelenting feminism of Imams Sultan Mohamed Shah and Shah Karim. The lifelong tireless labors of Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah to advance the cause of his female followers, and that of Muslim women generally, are readily acknowledged today by the Jamat and by Ismaili women in particular.

My beloved mother, whose life I have distilled into the few photos below, generously and readily applauded these remarkable advances made by today's Ismaili girls and young women. But she could not avoid wondering whether she had anything in common with them other than the foundational principle, namely, that each Ismaili forges a personal and private link with the Imam. Nor could she avoid questioning whether her own life experiences and Satpanth faith had anything inspirational to offer these young women with their uncompromising and jealously guarded commitment to their autonomy and self-sufficiency.

For their part, the young women in the Jamat regard the life experiences of their mothers and grandmothers with a benign, if not altogether condescending, respect and tolerance. But very few of them are convinced that these “old school” women have any lessons to teach them on “how to be an Ismaili woman” in the modern Euro-American world. I suspect that they would find my beloved mother's life not just alien but irrelevant to their own lives and circumstances.

As I describe below in greater detail, my mother's life was marked to an exceptional degree by much abuse, suffering and hardship. Yet throughout she remained capable of showing compassion, generosity, self-sacrifice and dedication not just to her abusers, but also to the Jamat and the wider public. Nor did she let these abuses and hardships stand in the way of discharging her many duties—domestic, Jamati, professional and civic—with competence, diligence and dignity.

What was the source of this extraordinary capacity? It was her Satpanth faith.

Satpanth

The word "Satpanth" (True Path3The Sanskrit word panth and the English word path are Indo-European cognates of each other, just as the words ginān (Gujarati, Hindi), jnāna (Sanskrit), gnosis (Greek), kennen (German) and know (English) are Indo-European cognates of each other.) is rapidly becoming an alien and unrecognizable word by the younger generation of the Jamat in Euro-American countries. But for my mother, and for generations of men and women of the Jamats in India (and Africa), Satpanth was a religious tradition (dharam) that had fulfilled the promise of Vaishnavite Krishna-centric religion, namely, that there would come to them—our ancestors—the Tenth Avatār (Dasmo Avatār4The word avatār is a noun form of the Sanskrit word whose Gujarati cognate is utarvun, that is, “to descend” or “to come down.” In Part Three of my remembrance of my mother, I will have more to say on this idea of “descent” (of Lord Vishnu) in Hinduism and the Quran’s claim that it is a “descent” (nuzūl), or that it has “come down” (nāzil), from Allah. It is semantically misleading to translate avatār as “manifestation” or “incarnation.”) of Lord Vishnu, and that this Avatār would be the Nizari5The Pirs introduced the Nizari Ismaili understanding of Imam Ali to the ancestors of present-day Indian-origin Ismailis. This Nizari understanding of Imam Ali differs in some fundamental ways from that of the Fatimid, Dawr al-Satr and pre-Imam Ja‘far al-Ṣādiq understandings of Imam Ali, as it does from that of the post-Mustanṣir Musta‘lian Ismaili tradition. Imam Ali. Since Krishna and Ram were avatārs of Vishnu, the Pirs centered Satpanth (and the Ginans) on the Ali-Krishna and Ali-Ram identity: each of these three figures—Ali, Krishna and Ram—had a different biological body, cultural context and personality, but they all had the same Spirit/Nur in these different bodies.

The Pirs regarded the entire religious and cultural history of India as rooted in, and springing from, the same spiritual universe from which the Abrahamic and Quranic religious landscape sprang forth. Both religious traditions—Vedic and Abrahamic—were different worldly religious and cultural forms of the same spiritual universe. With this fundamental understanding of the same spiritual source of the two formally different and superficially incompatible religious traditions, the Pirs were free to reach back to the primordial origin events of Vedic religion and recognize the religious personalities, beliefs and practices—cosmologies, eschatologies, doctrines, rituals, mythologies, and so on—as expressing the same spiritual realities that the Abrahamic and Quranic religions expressed.

The Pirs' spiritualist conception of Indian religious history is part of Prophet Muhammad's spiritualist conception of human history, namely, that if one steps below the surface of human social history, one discovers that there is only one spiritual world—one spiritual continuum—below the religious and cultural diversity of humanity. None other than Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah articulated this insight in the following succinct words:

Mohamed…by admitting that no people, race or nation had been left without some kind of divine illumination, gave his Faith universality in the past, and in fact, made it co-existent with human history.

The Pirs brought this insight of Prophet Muhammad to the Indian component of human history and taught it to our Satpanth ancestors. This spiritualist conception of human history—of humanity's religious and cultural diversity—as expressed by Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah, is not susceptible of academic approaches because the academic disciplines rest on tacit materialist secular-humanist principles that deny the spiritual world any agency in the dynamics of history and human social evolution. They therefore confine themselves to the study of forms, and they admit of no other causality than that obtaining among forms.6By "forms" I refer to the respective subject matters of the disciplines in the humanities, social sciences and the natural (physical and biological) sciences, and to the several applied and practical disciplines that rest upon these three basic components of the World of Learning. One very influential approach today to the study of religion is anthropologist Clifford Geertz’s notion of religion as a “cultural system,” a notion that has, derivatively, spawned the study of religion as a “cultural expression” that is then subject to the forces (forms) of history—that is, to political, economic, military, legal, social, intellectual and other forms.

This, in a nutshell, is the foundational insight that guided the Pirs gyroscopically through the otherwise bewildering thicket of Indian religions, mythologies and intellectual traditions and enabled them to engender the fusion7I object to such words as "syncretism" and "synthesis" for how Satpanth brought (or put) together Nizari Ismaili Islam and Hinduism. I will elaborate on this objection in Part III of my remembrance of my mother. of Nizari Ismaili Tariqah and Vedic religion into Satpanth.

Today, the Jamat is undergoing a historic and fateful reconceptualization of the Ismaili Tariqah whose long-term consequences cannot be discerned with clarity or certainty. The core of this reconceptualization consists in making the Quran the sole de jure and de facto supreme Scripture for all historical and future (new) Ismaili traditions. The primary motivation for this reconceptualization seems to be the (pressing) need felt by the institutional leadership to anchor the Islamic bona fides of the legitimacy of the Ismaili Imam's religious and spiritual authority in the one and only source that is recognized by the Ummah as the supreme authority over all Muslims: the Quran.

This perceived need has arisen because there are two Ismaili historical traditions8By "Ismaili historical traditions" I mean, firstly, the several Nizari Ismaili traditions (as distinguished from the Musta‘lī traditions) and, secondly, those Nizari traditions that have continued to recognize Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah and Shah Karim as their Imam. From a strictly historical and phenomenological perspective, the Imam Shahis and present-day Khoja Sunni and Khoja Ithnashari (Ithnā ‘Asharī) communities are of Nizari Ismaili provenance, even though they disavow Imams Sultan Mohamed Shah and Shah Karim as their Imam. I do not include them in the expression “Ismaili historical traditions” in this essay.—as of our present state of knowledge—in which the Quran has not, historically, enjoyed de facto supreme scriptural authority.9This and the next few paragraphs offer what I describe as phenomenological distillations of trends in the Jamat that I have observed over the past few decades. I hope to offer a fuller elaboration of these remarks in a future article. The first of these is Satpanth, in which the Vedas and their derivative and subsidiary traditions—spiritual (Vaishnavite bhakti), legal (dharma as defined by Manu's Laws10The older and native title for Manu’s text is Mānavdharmashāstra, whereas the colonial-era title that became popular in Europe is Manusmrti.) and mythological (Mahābhārata, Rāmāyana, Purānas, etc.)—enjoyed de facto supreme scriptural authority. All these traditions were seamlessly fused together into the Ginans by the spiritually inspired creative genius of the Pirs. The Ginans thus became and remained, until the contemporary project to reconceptualize and reformulate the Ismaili Tariqah, the de facto supreme scripture for Satpanth Ismailis.11It is therefore incorrect to describe or label the Ginans as "religious poetry" or "sacred lyrics," just as it is incorrect to describe or label the Quran as "religious poetry" or "sacred lyrics" (the Quran vehemently denies that it is poetry). The Ginans are the scripture (shāstra) of Satpanth in the same way as the Quran is the scripture of Islam. The Quran is the de jure as well as de facto scripture of Islam. In the case of Satpanth, however, the Quran is the de jure scripture but the Ginans are the de facto scripture. What counts in practice is the de facto scripture.

The second Ismaili historical tradition in which the Quran has not served as the de facto supreme scripture is that of the Pamir-Himalayan Ismaili tradition that traces its founding to the great Iranian Ismaili scholar, poet and dā‘ī, Nāṣir Khusrav (henceforth, Nasir Khusraw, d. 1088). Just as the Ginans were the de facto supreme scripture for the Satpanth Ismailis, so were Nasir Khusraw's poetry and expository doctrinal writings the de facto supreme scripture for the Pamir-Himalayan Ismailis.12We owe our current state of knowledge of this Ismaili tradition to the American anthropologist Jonah Steinberg's ethnographic study, Isma‘ili Modern: Globalization and Identity in a Muslim Community (2011). I will offer an in-depth discussion of this book in a future book review article.

Thus the impact of the contemporary trend toward an exclusively Quranocentric reconceptualization of the Ismaili Tariqah is most fateful for these two traditions. In the case of Satpanth, all Krishna-centric (and, ultimately, Vedic) content and references in Satpanth beliefs and practices have been, and are in the process of being, replaced with exclusively Quranocentric names, connotations and references.

For example, the Vedic-rooted vocabulary for spiritual master or guide (swāmi, nāth, guru, sāṅhīāṅ, deval, bālam, morāri, etc.) has now come to refer exclusively to Imam Ali and the succeeding Imams leading up to Shah Karim. Among the important shifts to Quranocentric practices I may mention the following: the term mandli has been replaced by the term majlis; Navmi Rāt mandli has been renamed Pānch Bār Sāl Majlis; Satī Mā Jo Rojo has been renamed Mowlā Jo Rojo; and so on. These are “as is” phenomenological observations on my part; I make no evaluative judgments on these changes since they are not germane to what I have to say about my mother below.13I will present a fuller treatment of the impact of this reconceptualization on Satpanth in Part Three of my remembrance of my mother.

Mahābhārata and Rāmāyana

There is one extremely important casualty of this reconceptualization of the Ismaili Tariqah: the two great epics of Indian religion and culture, Mahābhārata and Rāmāyana, are excluded from it. Both epics are part of the historical Satpanth tradition. The central male divine figure in Mahābhārata is Krishna, whereas the central male divine figure in Rāmāyana is Ram. The Pirs reconceptualized these epics as the life stories of Imam Ali by spiritually recognizing Krishna and Ram as Ali—and, conversely, spiritually recognizing Ali as Krishna and Ram. The Pirs then included in their Ginans stories from these two epics because, to them, they were stories involving Ali.

For Tajbibi, my mother, these epics were an integral component of her Satpanth dharam. In particular, two archetypical female personalities in these epics were destined to become very influential in her life: Draupadi in the Mahābhārata, and Sita in the Rāmāyana.

Draupadi in Mahābhārata

Draupadi has represented, for Indian women through the centuries, deliverance from suffering, abuse, humiliation, and the crushing of the spirit. In the Mahābhārata, she pays the penalty when her easily-duped Pāndava husbands lose the dice game against the cunning Kauravas. The penalty is that she should be disrobed in front of the assembly. Panic-stricken at the thought of being stripped naked, she cries out to Krishna to preserve her honor (lajā in the Ginan by Pir Abdul Nabi). Krishna is not present physically but hears her cries (venti) spiritually, and instantly comes to her rescue.14As Dushasan pulls at her sari to disrobe her, Krishna replenishes the sari by the exact length that has been pulled, with the result that Draupadi remains fully clothed all the time. Dushasan carries on pulling at the sari but eventually becomes tired and gives up.

Sita in Rāmāyana

Sita, on the other hand, teaches Indian women how to suffer. She is the archetype in Indian culture of the dedicated, self-sacrificing and silently suffering wife whose husband and in-laws (sasurāl) subject her to one form of cruelty upon another. Sita patiently and silently bears this suffering while remaining compassionate, generous and altruistic toward others who come to her for help.

My mother instinctively experienced her oppression at the hands of her merciless in-laws as Sita's oppression at the hands of her in-laws, and she instinctively responded to her oppressive situation by drawing on the example Sita had set for her Indian sisters.

Through all her different types of responsibilities—wife, mother, daughter-in-law, sister-in-law, breastfeeding volunteer at the Diamond Jubilee (1946), administrative aide at the Ismaili Mission Centre, sister and mother to Mission Centre students, teacher, founder/general-secretary of a civic organization, sister and mother to upcountry boarders (boys and girls), Jamati volunteer, library committee member, "support staff" to a scholar-preacher husband, travel companion, host to daily visitors, and so on—Tajbibi unimpeachably lived up to the ideals set for her by Sita: to suffer in silence yet be compassionate, generous, kind, and always accessible to those who came to her for help.

My mother often said to me, in a pained and resigned tone, Kaun sunegā meri kahāni? [Who will hear my story?] Would she have asked this question had she believed that the young women in the Jamat looked to her life experiences and Satpanth faith as sources of inspiration for their own lives as Ismaili women in the modern era?

Later in this essay, in the concluding Epilogue, I will return to this question.

Photo Essay

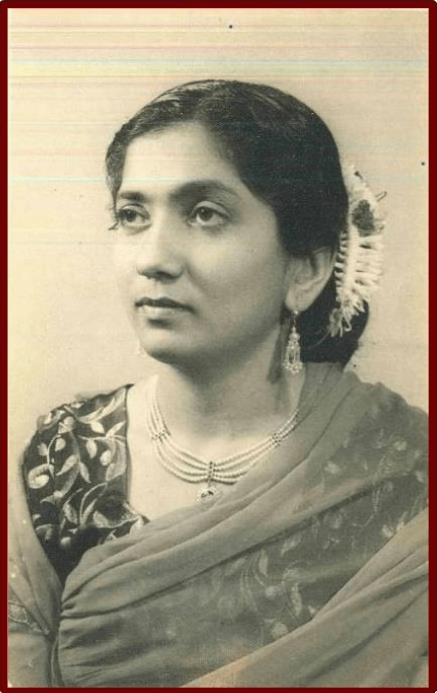

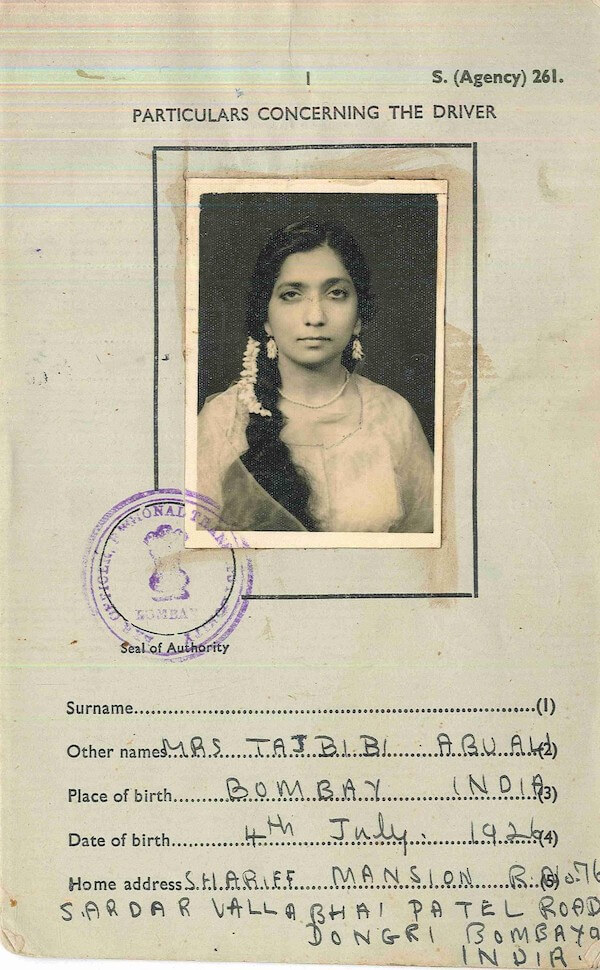

Tajbibi Muradali Juma was born in Mumbai on July 4, 1926. Her mother, Rehmat, was from Zanzibar. Her father, Mohamed Muradali Juma, was a senior missionary in the Mumbai Jamat. His family had remained loyal to Imam Aga Hasanali Shah during and after the famous Khoja Case (Aga Khan Case15The historic Khoja Case had vindicated the claim of Imam Aga Hasanali Shah that he was the latter-day Tenth Avatār (Dashmo Avatār) that the Pirs had presented to the ancestors of the Khoja. This claim was the basis of his claim that he was, therefore, the rightful legitimate spiritual leader, the Naklanki, of the Khoja community. Contemporary scholars of the Khoja Case now refer to it as the Aga Khan Case, the title of Tina Purohit’s 2011 book. I will discuss this book in a future review.) in the 1860s.

Photo 1

This famous photo was taken in Mumbai within days after Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah became Imam in 1885. He is surrounded by Jamati leaders, among whom was Tajbibi's grandfather, Muradali Juma. He is standing seventh from the right, face partially obscured, with only the right side of his moustache and beard visible. Courtesy Yasmin Karim.

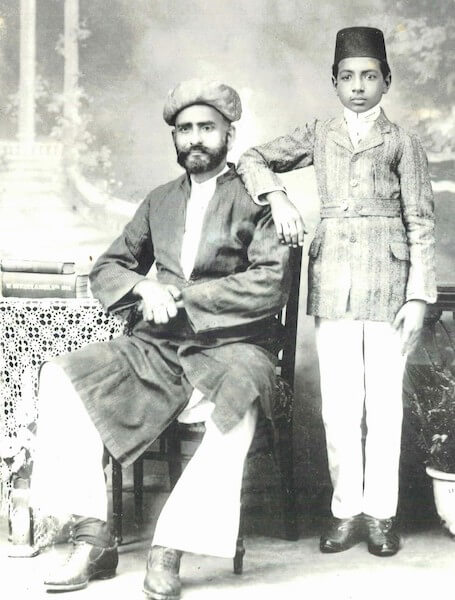

Tajbibi's grandfather, Muradali, used to accompany his father Juma on Imam Aga Hasanali Shah's hunting expeditions. One day the young Muradali picked up the Imam's hunting rifle and accidently triggered the gun, which blew away the top half of all his fingers on his right hand.

Photo 2

Muradali Juma with his son Mohamed (Tajbibi's father). All the fingers of his right hand are missing their top half. Abualy Collection.

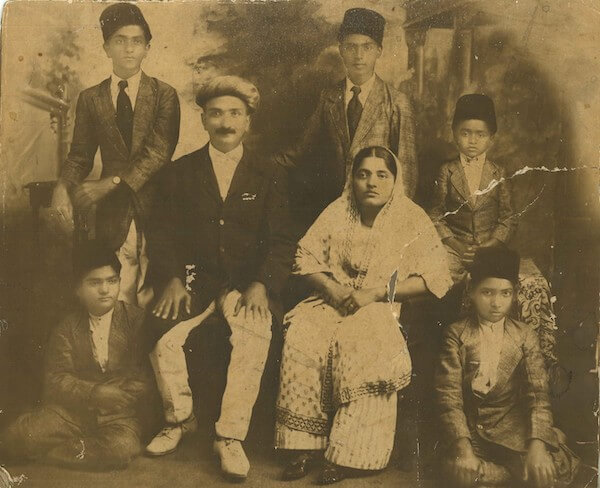

Missionary Mohamed Muradali used to travel to other Jamats to deliver waezes (sermons). He also carried out mission work (da‛wa) among the Untouchables. Over the years, Missionary Mohamed and Rehmatbai ended up adopting five orphans, three of them Untouchables.

Tajbibi's mother, Rehmatbai, was a simple unschooled woman. But she had a heart of gold and was a driving force in the decisions regarding adoptions. Nothing illustrates clearly her astonishing compassion than the story concerning one of her adopted children, whom they named Sadru.

Missionary and Rehmatbai Muradali were walking along a Mumbai street one day when they spotted an infant boy lying on the sidewalk. He had been abandoned and was naked and lying on the ground in his own excreta. Rehmatbai stopped and told her husband that she had decided to adopt the little boy. The [now-deceased] Sadru became Tajbibi's adoptive brother. Rehmatbai would add to the household by adopting another boy a few years later.

Photo 3

This family photo was taken before Tajbibi was born: Missionary Mohamed Muradali with his wife Rehmat and their three sons and two adoptive sons. Ramzan, the eldest son, is standing to the left. Standing behind Rehmatbai is the elder adoptive son, and the small boy standing to her left, behind her, is Shams, the youngest son. Seated by the feet of Mohamed Muradali is Jaffer, the second son. Seated to Rehmatbai's left is the adopted Kaderali Patel, who grew up to be a missionary and was appointed religion teacher to Princes Shah Karim and Amyn Mohamed by Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah. Abualy Collection.

Photo 4

Tajbibi's parents: Missionary Mohamed Muradali Juma and Rehmatbai Muradali Juma. Ca 1960s. Courtesy Yasmin Muradi.

Missionary Kaderali Patel

One of the Untouchable adopted boys was Kaderali Patel. This young boy would accompany Missionary Mohamed on his waez tours and was inspired to become a missionary himself. Missionary Mohamed trained the young Kaderali to become a preacher. Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah subsequently instructed the young missionary to go to East Africa.

Photo 5

This photo, taken in the late 1940s or early 1950s, shows Missionary Kaderali Patel (seated, center) with fellow missionaries Gulamhussein Juma (standing), Abualy Alibhai Aziz (seated, left) and Amirali Khudabux Talib (grandfather of Malik Talib, former President of the Aga Khan Council for Canada). The Talib family has a long distinguished record of multigenerational devoted service to the Imam and Jamat. Abualy Collection.

Later, Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah appointed , Tajbibi's adoptive brother, as religion instructor for his young grandsons Prince Karim (the present Aga Khan IV) and Prince Amyn Mohamed. The young princes were living in Nairobi during World War II. Missionary Patel traveled to Nairobi to discharge his duties.

Academic Award at School

Tajbibi attended the Ismaili community's primary school in Dongri. She remembered it as a three-floor building. This building is most likely the building housing the Diamond Jubilee Girls' High School today, which took over from the primary school in 1947 (the building itself was built in 1925).16I want to thank Shamim Suryavanshi of Mumbai for her generosity in expending time, thought and labor to research the history of this school building on my behalf.

In those days, schooling ended at the 7th grade. Upon matriculation, Tajbibi received an English novel, Black Beauty, in recognition of her academic excellence. In this remarkable novel, written in 1877, the English author Anna Sewell looks at human society through the eyes and experiences of a horse. The horse complains about all sorts of cruelties that humans inflict on horses. Sewell became an advocate for the humane treatment of animals. Black Beauty has become to the animal rights movement today what Mary Wollstonecraft's A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) is to the feminist movement.17Was Sewell familiar with the story in the Rasā’il of Ikhwān al-Safā’ in which the animals complain to the king about human cruelties against them? Research into this question would make for an ideal BA honors or an MA thesis.

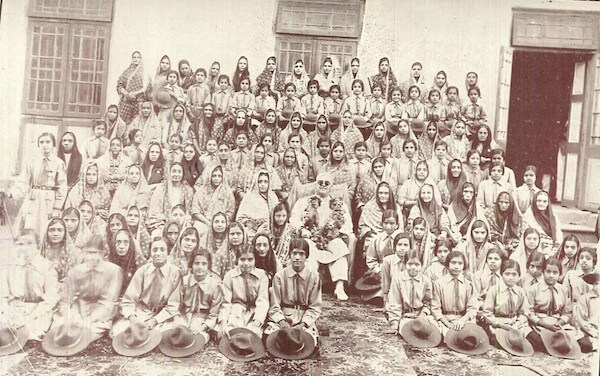

Girl Guide

Tajbibi was a Girl Guide in the Dongri Jamat. In 1935, to mark the occasion of Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah's Golden Jubilee, the Imam posed for a photo with the Ladies Volunteer Corps and Girl Guides of the Mumbai Jamat.

Photo 6

Tajbibi was a 9-year-old Girl Guide (seated on the floor in the front row, third from the left in the right half of the row). Her mother, Rehmatbai, was a volunteer. She is standing in the row behind the Imam's row, fourth from the right. [Photo from Position of Woman Under Islam, by Syed M. H. Zahid Ali, 1935. Foreword by Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah. Abualy Collection.]

Photo 7

Tajbibi as captain of the Girl Guides of the Dongri Jamat. Early 1940s. Abualy Collection.

Missionary Mohamed Muradali and the Recreation Cub Institute

Tajbibi's father, Missionary Mohamed Muradali Juma, went on to become one of the most respected and revered missionaries in the Indian Jamat. He was a senior member of the Recreation Club Institute that Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah had formally inaugurated in 1923 as a multipurpose institution engaged in religious, social and economic activities.18For a very valuable entry point into the origins and activities of the Recreation Club Institute, see the article “Recreation Club Institute” in Encyclopedia of Ismailism by Mumtaz Ali Tajddin Sadik Ali. This article is also accessible at http://www.ismaili.net/heritage/node/10467. Mumtaz Ali Tajddin Sadik Ali is an unsung and unappreciated hero of the Jamat. He has devoted his entire life singlehandedly publishing an astonishing number of books on the Ismaili Tariqah. The Recreation Club Institute is crying out for a doctoral dissertation by some enterprising young Ismaili scholar. The Institute served as a mutual support center for the missionaries, who sought advice and knowledge about Satpanth, Ginans and the Ismaili Tariqah from each other.

Among the notable colleagues and friends of Missionary Mohamed were missionaries Khudabux Talib (great grandfather of Malik Talib, former president of the National Council for Canada), Alidina Asani (grandfather of Professor Ali Asani of Harvard University), and Chief Missionary Husseini Pirmohamed Asani (step-brother of Alidina Asani).19Thanks to Professor Asani and President Talib for providing helpful details about their respective relatives.

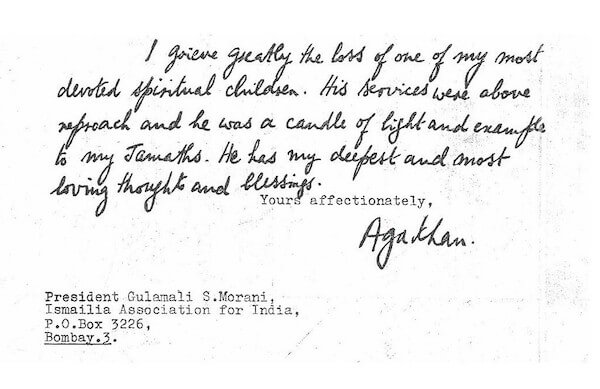

Following the passing of Missionary Mohamed Muradali in 1965, the Imam sent a letter of condolence and blessings for the late missionary and his family (below). The Imam described Missionary Mohamed Muradali as a "candle of light."

Photo 8

In his February 14, 1966 letter of condolence and blessings on the passing of Missionary Mohamed Muradali, Mowlana Hazar Imam added the above handwritten special message below the typed text of the letter (which is not reproduced here). Abualy Collection.

Tajbibi Marries Alwaez Abualy

Alwaez Abualy had come south from Amritsar to Mumbai to study at St Xavier College (University of Mumbai). The young Urdu-speaking Punjabi met Tajbibi at the Recreation Club Institute, where she had gone with her father, Missionary Mohamed Muradali. They were married on June 27, 1943.

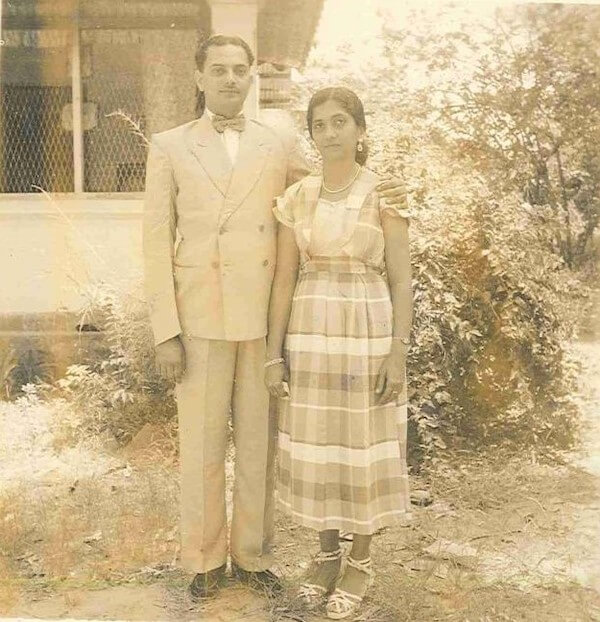

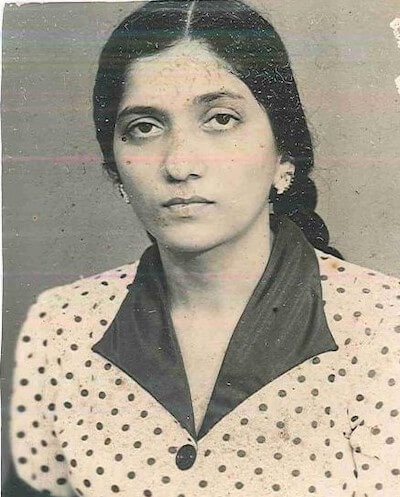

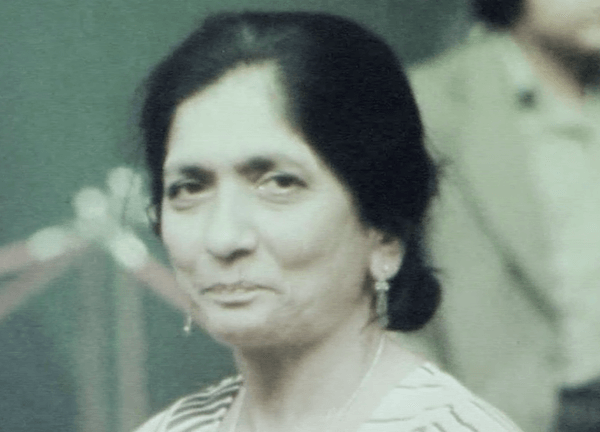

Photo 9

Tajbibi was 16 when she posed with her mother for this photo. She would be married to Alwaez Abualy the following year. Abualy Collection.

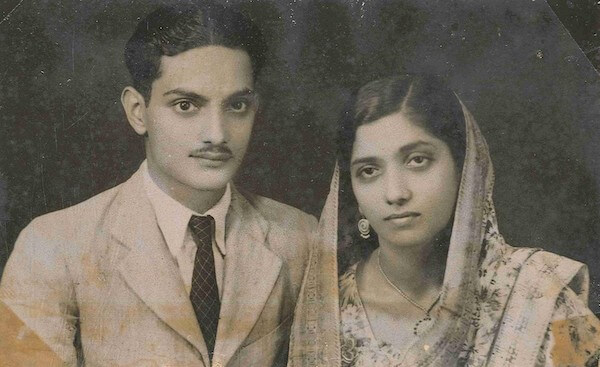

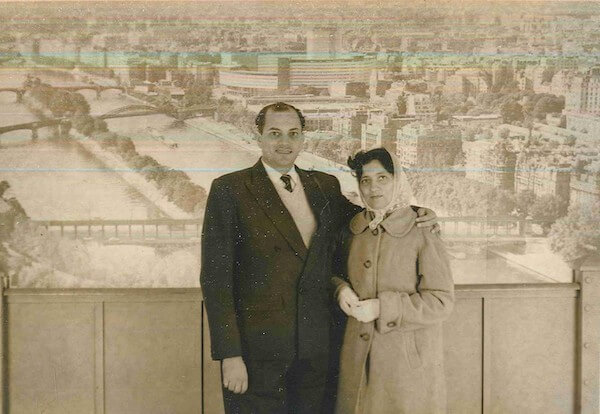

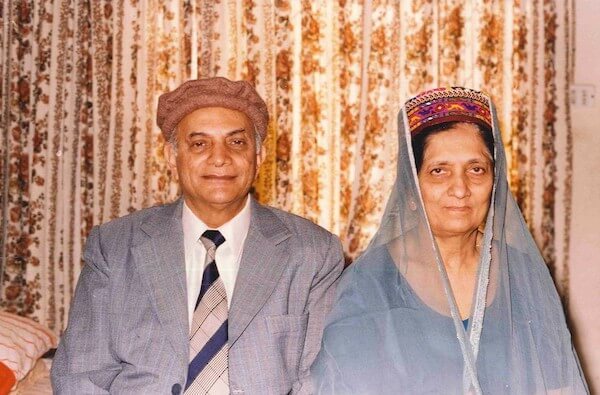

Photo 10

This photo of Tajbibi and Missionary Abualy was taken on July 4, 1943, Tajbibi's 17th birthday, one week after their wedding in Mumbai on June 27, 1943. Abualy Collection.

Foretaste of Abuses to Come for Tajbibi

A life-changing humiliating, traumatizing and degrading shock awaited Tajbibi as she arrived at her in-laws' home in Amritsar. Her mother-in-law, who had wanted her son to marry the Punjabi girl she had chosen for him, prohibited Tajbibi from using the family toilet. She was forced to use the servant's toilet. In a flash, Tajbibi's world turned upside down. Amritsar remained an unhealed gash in her soul for the rest of her life.

Tajbibi was the youngest child and only daughter in her family. Her brothers were very loving, caring, and protective of her. They were her eager servants ready to do whatever she wanted. She was their rāni (princess). She was also blessed with sisterly bonds with the girls in the five-floor building (Shariff Mansion) that her family lived in. One of the families in the building was a Jewish family. They were known affectionately in the neighborhood as Bani Israel. Their daughter Rachel and Tajbibi were the closest of friends, and they played and spent time together. Tajbibi was a much-loved popular and respected girl in the Dongri Jamat, in which she had been appointed captain of the Girl Guides. The school was another nurturing community of girls and teachers that Tajbibi grew up in. Girls and boys treated her as their sister, and adults regarded her as their daughter.

Nothing in this Mumbai background had prepared her for the catastrophe that ambushed her—an innocent seventeen-year old girl—as she arrived with her Punjabi husband at her in-laws' residence in Amritsar.

Worse was to follow, as I describe later, below.

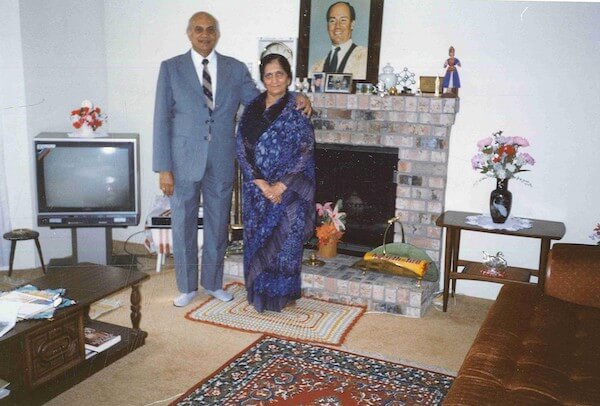

Photo 11

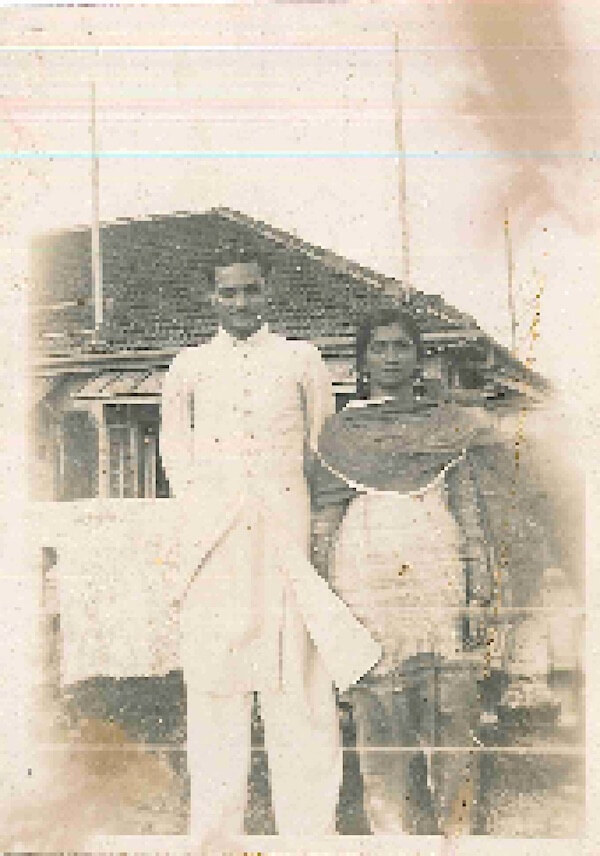

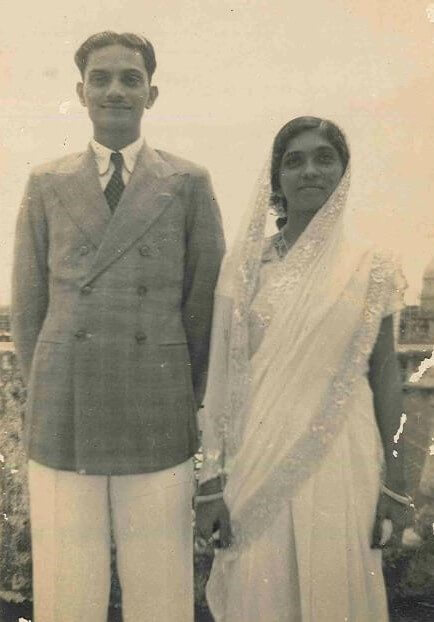

Tajbibi and Alwaez Abualy soon after their wedding in Mumbai in June, 1943. Abualy Collection.

Photo 12

Tajbibi and Alwaez Abualy before their migration to Africa, ca. 1943-45. Abualy Collection.

Photo 13

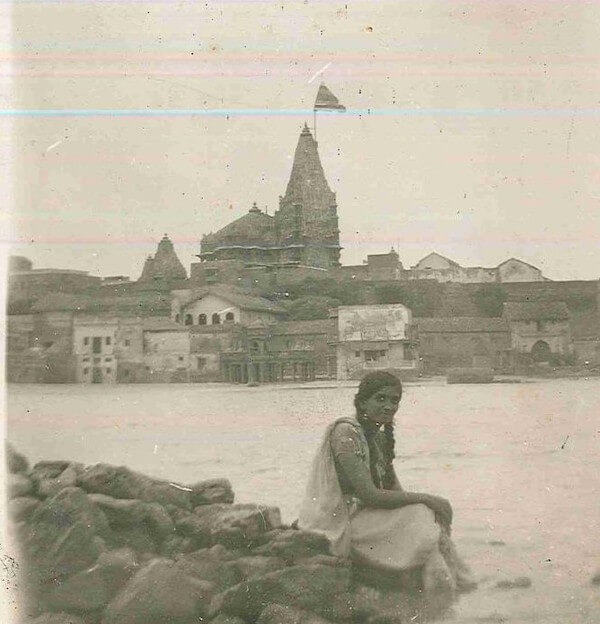

She wrote on the back of the photo: "We, my brother Jaffer and a friend Sadrubhai were travelling to Karachi when we had a stop over at a Holy Place Dwarka. I am expecting with Mohamed." The temple in the background is Dwarkhadhish Temple.20Dwarka is mentioned in the Mahābhārata. According to Hindu legend, Dwarka was the site where Krishna built his palace. The temple itself was built on Krishna’s palace by his grandson Vajranbh. Childless and pregnant women visit the temple to seek Krishna’s blessings. My mother was well aware of this role of the temple when she visited it. one of the four ancient temples in the city, which is located in northwestern Gujarat. Abualy Collection.

Migration to Africa

Soon after arriving in Mumbai to study at the University of Mumbai, the 20-year old young Punjabi Alwaez joined the Waezeen group and began delivering waezes (sermons). The Kutchi and Gujarati-speaking Mumbai Jamat had not seen or heard anyone like him before. His powerful Urdu sermons (waezes) took the Jamats by storm. He had become a sensation.

Already several years back in Amritsar, Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah, on one of his visits to the Jamats in Punjab, had recognized in the young 14-year-old boy the makings of an Alwaez. He ordered—hukm, as my father would proudly tell me—the young boy to become a missionary: Abualy, tum missionary bano ("Abualy, you become a missionary."). For his Mumbai visits, the Imam also appointed him as the transcriber of his Farmans and asked him to accompany him to the various Jamats in the greater Mumbai area. The Imam delivered Farmans in Urdu, which was Alwaez's native language (alongside Punjabi).

A fateful moment for Tajbibi arrived when Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah appointed Alwaez Abualy as director and lecturer of the newly created Ismailia Mission Centre in Dar es Salaam, Tanganyika (Tanzania) to train home-grown Waezeen.

Africa had become something like a Promised Land for the numerous communities on the west coast of India (Goans, Sikhs, Memons, Hindus, Muslims, others). There had developed within each of these communities a "scramble for Africa," an organized movement to send young men and women to Africa where they would settle and transplant the religious and social institutions of their respective faiths.

For Tajbibi, Africa represented a mixed blessing. On the one hand, she did not want to sever her ties with her parents and siblings. On the other hand, she welcomed the prospect of escaping from the abuses of her in-laws. The Imam's appointment of Alwaez Abualy was fateful for Tajbibi because she did not have the faintest clue as to what the future life in Africa had in store for her.

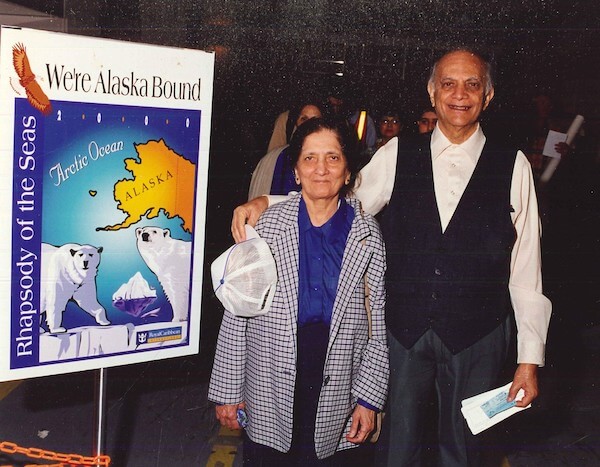

Tajbibi, Alwaez Abualy and I—six months old, for I was born in December 1945 in Mumbai—sailed for Dar es Salaam in July 1946, arriving there just in time for the Imam's Diamond Jubilee celebrations in August.

Suckling Babies at the Diamond Jubilee of Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah

The very first major event in which Tajbibi volunteered immediately upon arriving in Dar es Salaam was the Diamond Jubilee of Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah in August 1946.

A most remarkable act of volunteerism during the Diamond Jubilee celebrations was the suckling of babies and infants by volunteer young mothers in the Dar es Salaam Jamat.

Ismailis arrived in Dar es Salaam from all parts of Africa, including South Africa. They were hosted by members of the Dar es Salaam Jamat. Among the guests were young mothers with suckling infants. In order to give these women the opportunity to take part in the many programs marking the historic event, young mothers in the Dar es Salaam Jamat volunteered to suckle the babies of their guest sisters. Tajbibi Abualy was one such volunteer who breast-fed several babies over the course of the celebrations.

I invite young women in the Euro-American Jamats to reflect on the enormity of this act of sacrifice by these women on behalf of their sisters-in-faith. Most of today's young women in the Jamat are likely to use the bottle to feed their babies (if and when they become mothers). What sort of sisterly bonds (dīn baheno) made such sacrifices not just a possibility but a no-brainer for my mother when today it would cause our young women to shrink in horror?

The Ismaili Mission Centre

As the wife of the director of the Ismaili Mission Centre, the 20-year-old Tajbibi found herself thrust into a range of administrative and social duties for which she had not been prepared but which she accepted and discharged with skill, grace, and compassion.

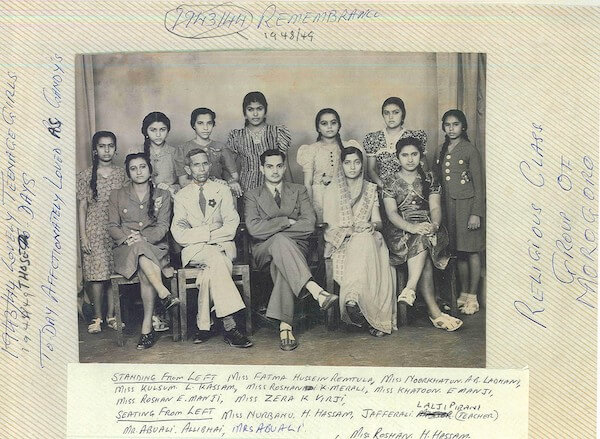

Photo 14

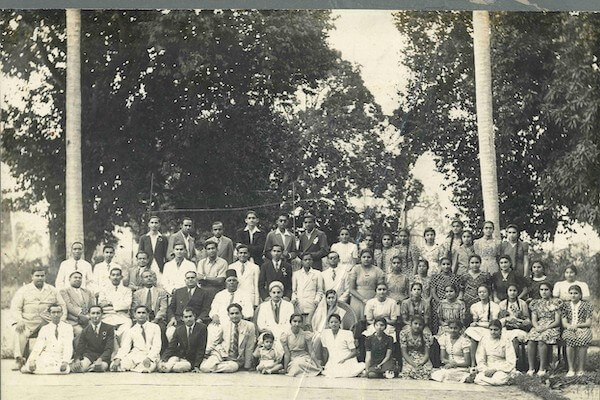

This photos is unquestionably one of the most important photos for the history of the Waezeen in Africa. Tajbibi and Alwaez Abualy are shown with students and officers of the Ismailia Mission Centre, Dar es Salaam, 1948 (or 1949). Notable among them: (Last row): Ismail Ibrahim (third from the left); Lord Amir Bhatia (fourth from the left, presently a member of the UK House of Lords). (Third row): Jaffer Sadiq (far left; Indigenous Ismaili); Alwaez Budhani (eighth from the left); Khanu Hussein Gulamhussein Harji (Moaiz Daya's Maasi). (Second row): Remtullah Walji Virji (third from the left); Jafferali Meghji (fifth from the left); Hussein Jessa Bhaloo (sixth from the left); Alwaez Abualy; Tajbibi Abualy; Gulibai Hirji (maiden name Gulbanu Alibhai Bhatia); Gulshan Sultanali Nazarali Walji (maiden name Gulshan Karmali Jaffer); Gulbanu (Bebla) Hassanali Ismail (Ismail Ibrahim's sister); Kulsum Kassam Sunderji; Fatma Nathoo Nanji (wife of Ismail Ibrahim); Roshan Walji Daya (second from the right, aunt of Moaiz Daya). (First row): Hasanali Walji (far left); Sadru Fatuma Parsi (second from the left); Alwaez Sultanali Nazarali Walji (fifth from the left; husband of Gulshan Sultanali Nazarali Walji); Mohamed Abualy Alibhai (child); Roshan Karmali Bhanji (next to Mohamed), and Shirin Karmali Bhanji (fourth from the right). [The following have helped to identify the individuals in the group: Gulibai Hirji, Lord Amir Bhatia, and Moaiz Daya.] Abualy Collection.

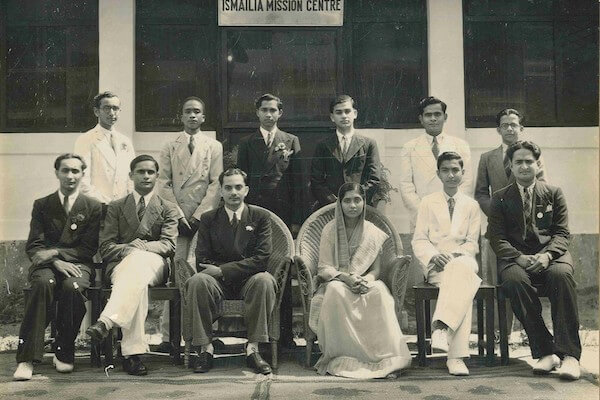

Photo 15

Some of the students of the Waezeen training program with Alwaez Abualy and Tajbibi Abualy. Notable among them was Jaffar Sadiq, the (black) indigenous Ismaili standing second from the left. Abualy Collection.

Tajbibi had to cater to men and women of different ages, and she had to be a competent, gracious and understanding host to all, a sister to some and mother to some, and an administrative assistant to the director, Alwaez Abualy—all at the age of 20.

Gulibai Hirji recalls (in a recent email to Mohamed): "The students at the Mission Centre used to call her ‘Mummy' and so did I. She was a Mom for all of us. Such a kind and beautiful Lady." Gulibai Hirji was one of the few young women who quickly coalesced around Tajbibi and forged close sisterly bonds (dīn baheno) with her.21An early reference to this popular East African fruit occurs in a diary entry of the Christian missionary, Chauncy Maples. The missionary records his efforts to learn Kiswahili. One of the words he sought to translate was “zambarau,” which he describes as “a famous Zanzibar fruit…something like a damson…The tree is one of the finest and tallest that grows on the island.” (Diary entry dated March 28, 1877, in Chauncy Maples: Pioneer Missionary in East Central Africa for Fifteen Years and Bishop of Likoma, Lake Nyasa, 1895, p85.) There is speculation that the word “zambarau” is derived from the Portuguese jambolāo, which in turn is rooted in the Sanskrit jambu. If this speculation is true, then Goa may be the likely source of this fruit found in East Africa.

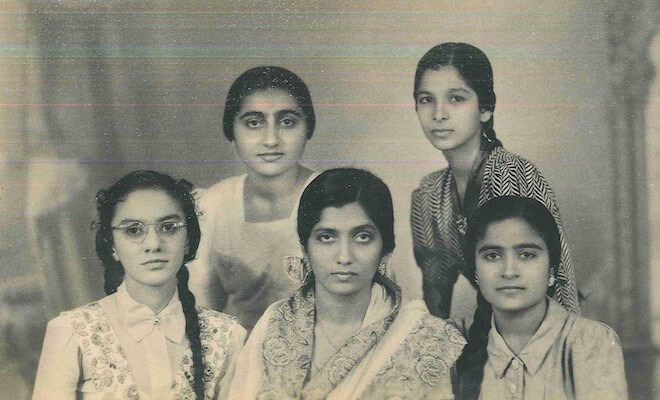

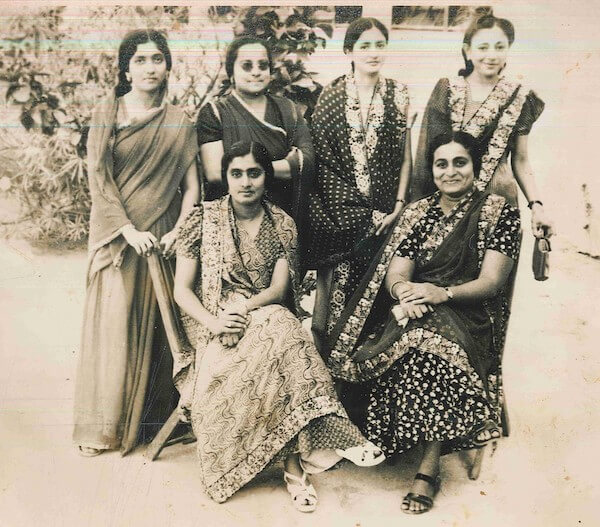

Photo 16

Tajbibi with her friends who were also students at the Ismailia Mission Centre. Kulsum Kassam Sunderji (seated, left), Gulbanu (Bebla) Ibrahim Ismail (seated, right; deceased), Gulibai Hirji (left, back row), and Gulshan Sultanali Nazarali Walji (back row, right). Late 1940s or early 1950s. Kulsum Kassam Sunderji and Gulshan Sultanali Nazarali Walji live in Vancouver; Gulibai Hirji lives in New York. Abualy Collection.

Photo 17

Another major source for a future history of Ismaili religious education in Tanzania: Tajbibi and Alwaez Abualy with students and teachers of the religious education class in Morogoro, Tanzania, 1948 or 1949. Abualy Collection.

Sundowners

Sundowners were occasional picnic-like events invented by the British. "Sundowner was a phenomenon of Colonial rule in India and in East Africa. It was initially started by the Brits, after 4 or 5 PM when they finished their work in government offices. It was always tea with cakes and biscuits. Later it converted into an evening affair with drinks and cocktails and savories. The Asians also adopted the sundowners to invite the white government officials and companies."22Thanks to Lord Amir Bhatia for this information.

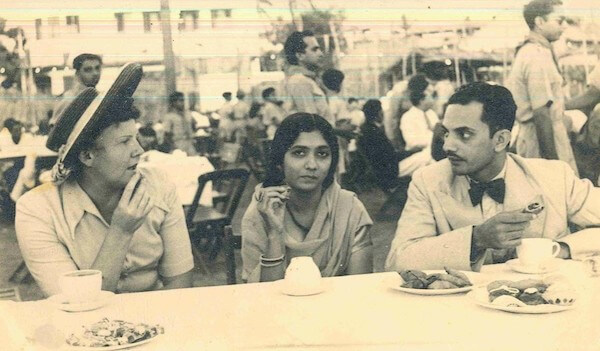

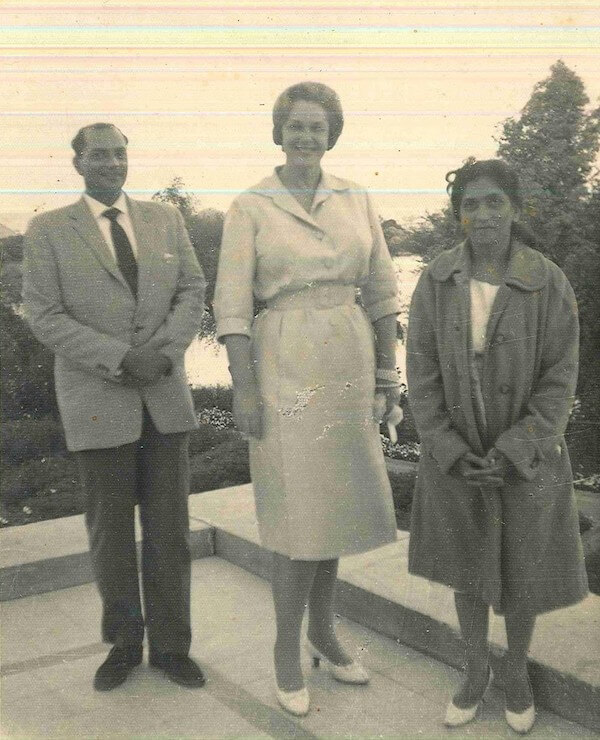

Photo 18

Tajbibi and Alwaez Abualy with a British lady at a sundowner in Dar es Salaam, late 1940s or early 1950s. The boy scouts in the photo suggest that this sundowner was hosted by the Ismaili community. Abualy Collection.

Elderly Swahili Mama Joins the Abualy Household

Concurrent with these responsibilities, Alwaez Abualy began to travel into the interior to deliver waezes (sermons) to the Jamats. Tajbibi was left behind to cope with the Mission Centre students, her own children (she was a mother of three young boys by 1948), and her teaching duties at the school.

The house that my parents moved into was a German-era derelict bungalow in the Upanga area of Dar es Salaam. It now belonged to a prominent member of the Jamat. Alwaez Abualy rented it from him. Upanga later became a stronghold of the Ismaili community in the wake of the new housing scheme launched by Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah. The first group of "Ismaili flats" in Upanga were settled in 1954. Our house was located deep in the bushes, surrounded on all sides with mango trees, tall coconut palms, the odd almond tree, and the zambarau23An early reference to this popular East African fruit occurs in a diary entry of the Christian missionary, Chauncy Maples. The missionary records his efforts to learn Kiswahili. One of the words he sought to translate was “zambarau,” which he describes as “a famous Zanzibar fruit…something like a damson…The tree is one of the finest and tallest that grows on the island.” (Diary entry dated March 28, 1877, in Chauncy Maples: Pioneer Missionary in East Central Africa for Fifteen Years and Bishop of Likoma, Lake Nyasa, 1895, p85.) There is speculation that the word “zambarau” is derived from the Portuguese jambolāo, which in turn is rooted in the Sanskrit jambu. If this speculation is true, then Goa may be the likely source of this fruit found in East Africa. trees that produced succulent bunches of fruit that looked similar to cherries.

The remote and inaccessible location of the house understandably created anxiety over security. A night watchman (askāri) was hired and three fierce attack dogs were brought to keep burglars at bay. With these security measures in place, Alwaez Abualy felt reassured that he could go on his Waez missions into the interior and leave Tajbibi in the safe hands of his younger brother, who was living with them.

There was one additional person in the house who provided reassurance and comfort to Alwaez Abualy and especially to Tajbibi. At the Aga Khan Dispensary—the Aga Khan Hospital had not yet been built—a diminutive Swahili (black) elderly lady, who worked as mid-wife at the dispensary and who had managed the births of my two younger brothers, was invited by Alwaez Abualy to retire and come live with us. Mama, as we fondly called her, was given her own private room (into which I later moved). Apart from helping Tajbibi in the kitchen and feeding us three young boys while Tajbibi was at school, she had no other duties.

Alwaez Abualy then did something truly remarkable. He gave Mama full authority to scold and discipline us, including beating us, if she saw fit. Mama never hit any of us, but she would shout at us if we misbehaved or did something she deemed carried hazard, like climbing the tall almond tree (which I was wont to do in a reckless spirit). I was at the receiving end of most of her scolding.

Mama was a frail short woman, full of wrinkles on her face that testified to years of extreme poverty and hardship. Yet, in what to me is one of the most amazing qualities about Alwaez Abualy, Mama was the only person in the Abualy household at the time who could scold my father without fear (his mother, of course, could do it too, but she joined the household later, as I describe below). This would happen if she felt that he had been too severe with me (I was becoming a discipline problem at home and school and had to be reined in through beatings and slaps to the face). Alwaez Abualy would instantly stop in his tracks, stand before her with his head bowed, and listen to her tirade (in Kiswahili) until she had said enough and walked away. He had given her the status of his own mother. His respect for Mama—who, technically, was a black African servant (āyah)—has remained with me as his most astonishing and noble qualities.

Mama's fortunes changed dramatically after Tanganyika (Tanzania) gained independence in December 1961. One day—sometime in 1962 or 1963—a government Land Rover carrying police officers showed up unannounced at our house. The officers alleged that a relative of Mama in Zanzibar had complained to them that we, the Abualy family, were mistreating Mama. They said that they had come to take her away and send her back to Zanzibar, which they claimed was her original home. To our great surprise, Mama refused to go with them and rejected their allegations against us. She told them that not only was she very happy living with us, but that she wanted to die "here" (at our house). The police would not hear of this. They forcibly seized her—she fought back at them!—and hauled her away.

We never saw Mama again. However, our night watchman, Sulemani, managed to obtain some information through his grapevine. He told us that Mama owned a plot of land (shamba, shāmbā) on the island. The young relative coveted it and cooked up the false charge of abuse as a way to draw Mama back to the island. What did this woman and her accomplices plan to do with her? Did they plan to kill her and grab the land? Did they plan to force her to place her thumbprint on the title document transferring ownership of the shamba to them? Sulemani could not obtain answers to these questions. We have remained in the dark ever since her forcible removal from our home. Curiously, the police never filed any charges against us prompted by these false allegations.

Photo 19

Tajbibi and Alwaez Abualy in front of their house, early 1950s. The upper half of the wall of the U-shaped living room was a wire-gauze net made from small diamond-shaped elements (as shown in the photo). At the bottom right corner, inside the living room (just to the right of Alwaez Abualy's upper right arm), was the PYE radio full of cathode ray tubes at the back. BBC World News at 9:00 PM every evening, after we returned from Jamatkhana services, was a fixture. The world news covered the first nine minutes, followed by five minutes of what the BBC called "Commentary," which was an opinion piece on some international issue delivered by a professor at a British university. Abualy Collection.

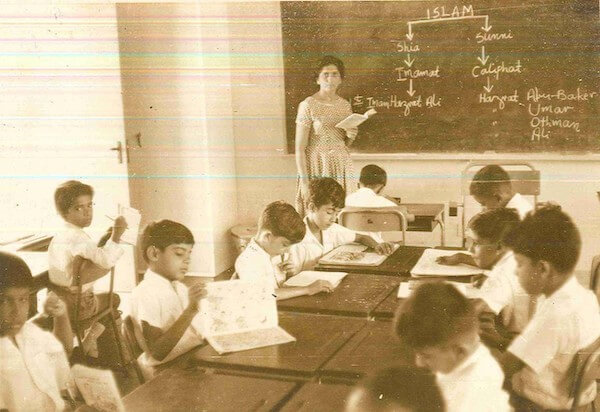

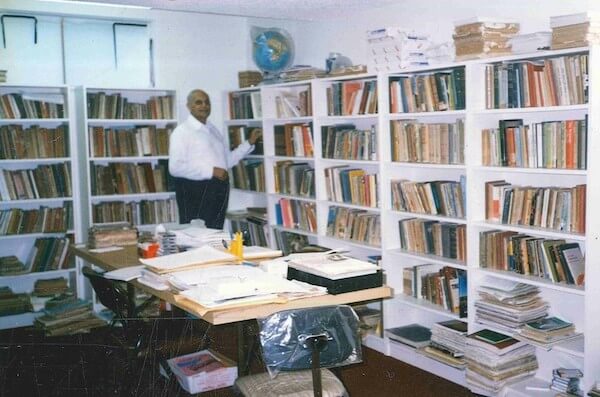

Tajbibi the Teacher

Tajbibi's formal education had extended to seventh-grade matriculation level only. But as soon as she arrived in Dar es Salaam, she was called upon by the community's education committee to join its primary-school teaching force because of a lack of teachers. She would end up teaching for nearly twenty years, finally retiring in the mid-60s. During that long period, she taught several generations of pupils (and secondary students), some of whom are leaders of our Jamati institutions today.

Tajbibi was not the only teacher whose schooling did not extend beyond the seventh grade. Most of her colleagues were similarly limited in their schooling. Indeed, when the Aga Khan education board hitched its curriculum to Cambridge University's curriculum for the colonies, the highest grade at the time was the eleventh grade (Form III). The school leaving certificate at Form III was known as Junior Cambridge School Certificate. The education of the administrators of the Aga Khan schools did not extend beyond the eleventh-grade Junior Cambridge School Certificate.

One notable school administrator was Razac Hassam, a fatherly kind man whom I used to visit at his store near Darkhana. He was the administrator of Tanzania's Aga Khan schools, yet his own schooling had ended at Junior Cambridge. In spite of these formal educational limitations, Razac Uncle (as I and my friends called him) had been very conscientious about his responsibilities and had done his due diligence in informing himself about A levels (Forms V and VI) and university education. He offered advice on post-secondary education with a combination of humility, knowledge and confidence, and he did not hesitate to offer advice to students like me whose formal schooling (Forms IV through VI) had outstripped his own.

When the new boys' school opened in 1958 on Cameron Road (later renamed United Nations Road) that linked Morogoro Road to Upanga Road near the Salendar Bridge, the school's entrance hallway carried a huge wooden plaque listing the names of Junior Cambridge alumni. There were no grade twelve (Form IV) alumni at the time. By 1964 the school had graduated its first batch of Form VI science students.

Photo 20

Tajbibi with fellow teachers of the Aga Khan Primary School, Dar es Salaam. Sakarben Lila, one of her closest friends, is seated to the left (Tajbibi has her hands on Sakarben's chair). Sakarben was a rock of emotional support for Tajbibi during her years of suffering. Already in this photo and the following photo, Tajbibi's unsmiling sad face and eyes betray her unhappy internal life. Late 40s or early 50s. Abualy Collection.

Photo 21

Tajbibi with fellow teachers at the Aga Khan Primary Girls' School, Dar es Salaam. Late 40s or early 50s. Abualy Collection.

Photo 22

Tajbibi teaching religion class at the Aga Khan Boys' Primary School, Dar es Salaam, mid-1950s. The dress ("frock," as it was popularly called) that she is wearing suggests that the photo was taken after 1952. In that year, Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah had circulated a photo of himself and Mata Salamat Om Habibeh that showed Mata Salamat standing beside the seated Imam, wearing a dress that reached just below the knee. The Imam wanted his women followers to adopt what he called "simple colonial" dress (he wrote his message on the photo). The impact of this Farman was instant and sweeping among young women and girls. Abualy Collection.

By today's standards, our university-educated young men and women may look back at these teachers with their seventh-grade and Junior Cambridge education with a kindly and condescending dismissiveness. They would be missing something important about these "blind leading the blind" teachers: these teachers more than made up for their lack of grade-twelve education by the immense personal effort they expended in self-study aimed at acquiring new knowledge. But they did more than that: they regarded each pupil as their own child and took a keen parental interest in their intellectual and moral development. They could do so because these teachers enjoyed the unconditional support of the parents and community institutions. [I will present a fuller treatment of this topic in Part Two of my remembrance.]

A Beloved Teacher Remembered by Colleagues and Students

As I have already mentioned above, Tajbibi would go on to serve as teacher for nearly twenty years. She taught boys and girls, and many of them remembered her fondly and came forward from all parts of the world to express their sorrow and offer their condolences when they learned that she had passed away.

Photo 23

Although she was based at the Aga Khan Primary School, Tajbibi occasionally came to the Boys' Secondary School as a substitute teacher. Here she is in the staff room of the Aga Khan Boys' Secondary School, Dar es Salaam, 1960. Abualy Collection.

Tajbibi was universally loved and respected by her colleagues. Her male colleagues at the legendary Aga Khan Boys' Secondary School—Mr Khan, Mr Kabir, Mr Fernandes, Mr Shaw, Mr Carvalho, Mr Almeida, Mr Kanga, Mr Gregory (the English principal), and others, all non-Ismaili)—showed tremendous affection for Tajbibi and treated her with great respect and fraternal solicitude. Of them all, it was Mr Khan, my physics teacher and class master in Forms III and IV, who held a special brotherly regard for Tajbibi, and when her hour of need arrived, it was to him that she turned for help. [I say more on this "hour of need" below.]

Her students and colleagues would fondly remember her even decades later. Two events, in particular, testify to the lasting respect and affection in which she was held.

The first event occurred on Zanzibar Island a few weeks before the Zanzibar Revolution in early 1964 (I was in Form VI). I and three other students from our school were selected to play for the Dar es Salaam cricket team in an intercity match against Zanzibar. We flew to Zanzibar. During our flight the team was entertained by the mellifluous singing of Oldies Goldies Hindi songs by Nazir Hussein from the Ithnashari team. The Jamati leaders of both Jamats—Dar es Salaam and Zanzibar—had worked together and arranged for the Ismaili students to be hosted by the famous Bhaloo family on the Island.

Next morning we headed for the Sayyid Khalifa Stadium, where the cricket match was to be played. When we arrived at the stadium, I was surprised to see Mr Gregory there. Mr Gregory had been the headmaster of our school in Dar es Salaam. We knew that he had left the school, but we did not know where he had gone. Here he was, in Zanzibar. I saw him chatting with some people. Suddenly one of the men pointed toward me. Mr Gregory turned and saw me. He walked over, greeted me and my fellow Ismaili students and told us how proud he was that the Aga Khan School had sent the largest contingent of players to the Dar es Salaam cricket team. He explained that he was now in Zanzibar because he had been asked by the administrator of Aga Khan schools to take over as headmaster of the Aga Khan school in Zanzibar.

Then Mr Gregory turned to me and asked me if I was "Mrs Abualy's son." He did not ask, "Are you Mohamed Abualy?" He asked me if I was Mrs Abualy's son. I said I was. Mr Gregory had a rugged freckled face topped by carrot-colored hair. True to form, as he always did, he wore khaki shorts and white shirt, the dress of colonial officers. He told me that he came to the stadium after he read my name listed (in the Dar es Salaam team) in the local newspaper. He said he wanted to meet me to tell me how much he remembered my mother, what a good teacher she was, and that he wanted me to convey to her his warm regards and respects.

The second event occurred in Toronto in early 2002. I was given a tour of the Khoja Ithnashari madrasa (Sunday) classes at the great Jaffari Masjid in Toronto. These classes were the equivalent of the Ismaili community's BUI (Bait Ul Ilm). There were separate classes for different age groups (separate for boys and girls), all the way for Grade 12 students.

My extremely warm, helpful and brotherly escort stopped at a class for the Grade 12 boys and asked me to wait outside as he walked in. He came out accompanied by the teacher, whose name was Raza. He explained to Raza that I was conducting research on religious education programs among Canada's Muslim communities, including the Ithnashari Jamat. He told Raza that I was from Dar es Salaam.

Raza turned to me and said that he had been a student at the Aga Khan Boys' Primary and Secondary Schools in Dar es Salaam. He said that of all the teachers who had taught him, there was one whom he still remembered (in 2002) because she was not only a very good teacher but also a very loving, caring and kind person.

Then Raza said, "Her name was Mrs Abualy. Do you know her?" It took me a few seconds to collect myself from the emotions that had overwhelmed me. "That is my mother you mention," I said, holding back tears.

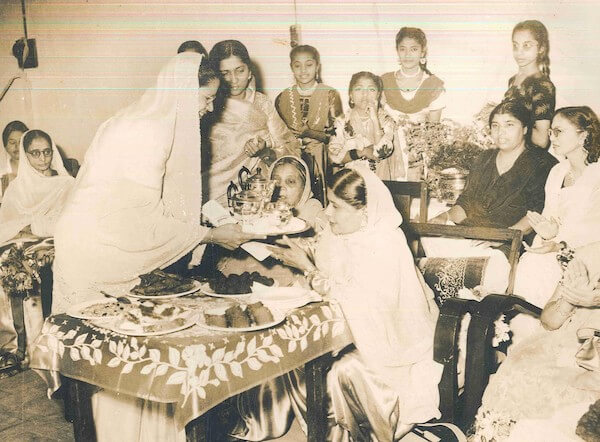

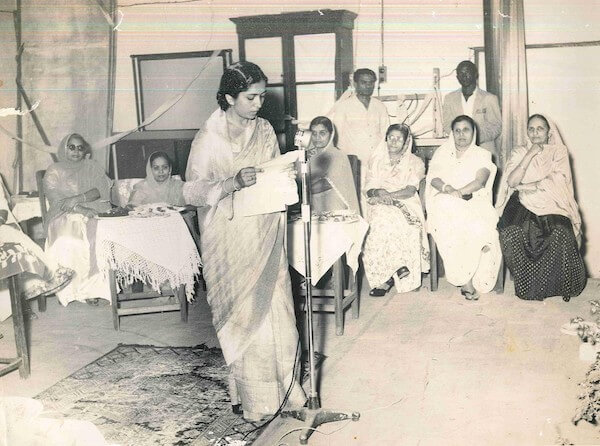

Civic Engagement: Founding Member of the Muslim Women's Association

Soon after arriving in Dar es Salaam and settling in her new home in Upanga, Tajbibi became active in civil society work by joining with some Muslim women to establish the Muslim Women's Association. She was elected its General Secretary.

One notable event organized by the Muslim Women's Association was a banquet in honor of Begum Siddiq Ali Khan, wife of the Pakistan High Commissioner to Tanganyika.

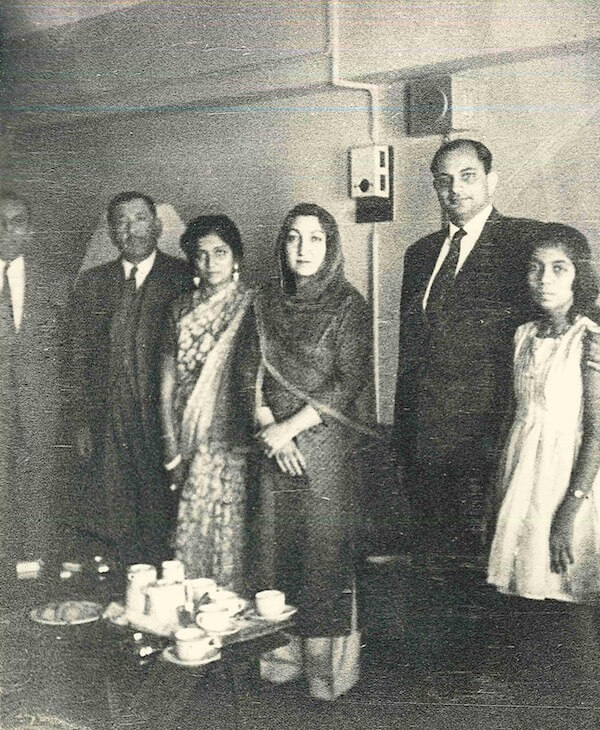

Photo 24

Tajbibi Abualy (standing, looking on) at a party organized in Dar es Salaam by the Muslim Women's Association in honor of Begum Siddiq Ali Khan, wife of the Pakistan High Commissioner, Nawab Siddiq Ali Khan. Early 1950s. Abualy Collection.

Photo 25

Tajbibi was one of the founders of the Muslim Women's Association in Dar es Salaam and was elected its general secretary. Here she is delivering a speech at one of the group's meetings. Late 1940s or early 1950s. Abualy Collection.

Photo 26

Tajbibi (front row, standing second from left), the general secretary of the Muslim Women's Association, welcoming Begum Siddiq Ali Khan (garlanded), wife of the Pakistan High Commissioner to Tanganyika, early 1950s, at the Aga Khan School in Dar es Salaam. Above the inner entrance is a Latin maxim that Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah had designated as the motto for all the Aga Khan schools. The words "Mens Sana In Corpore Sano" mean "A Healthy Mind in a Healthy Body."

Years of Psychological Abuse, Humiliation, Hardship44This extended section does not include any photos, which reappear in subsequent sections.

I come now to that part of Tajbibi's life which has proved very vexatious for me and that has presented me with a moral dilemma, a dilemma that I, as her son who has committed himself to giving her the voice that she did not have in life, have had to grapple with and resolve, not to anyone's satisfaction, but to what I intuit as my mother's satisfaction.

Stated in plain language: I cannot speak about the abuses that were inflicted on my beloved mother which she, Sita-like, silently endured, without in some way drawing into my narrative of her life those who inflicted on her these torments and cruelties. The events and incidents concerned reach back to the mid-50s, although their impact on my mother left a permanent wound in her soul. Some of the perpetrators are no longer with us, whereas those who are still alive will clearly resent being dragged into the public eye. All I will say to them is that it is impossible for me to leave out from my account of her life this abuse, which was central to how she experienced her family life. What I have to say is not mere hearsay on my part. I was old enough at the time to have witnessed what was happening to my mother, and to have understood that what was happening to my mother was abuse pure and simple. Even I was subjected to physical abuse by some of the in-laws.

Before I proceed with an account of this part of her life, I want to say a few words about two aspects of Tajbibi's marriage that provide a partial and mitigating explanatory cultural framework for why she suffered these abuses. This framework does not entirely exonerate the perpetrators, but it does at least enable us to view them and their actions as products of deeply entrenched social structures, beliefs and norms in traditional Indian society.

The sasurāl-bahu Model

The first of these two aspects is the culture governing the daughter-in-law's life within her in-law family. The social form of this relationship is known as the sasurāl-bahu relationship. The in-laws are the sasurāl, and the daughter-in-law is the bahu. The sasurāl-bahu model is a structural feature of the Indian family. It is ubiquitous all over India. Structurally, the girl physically must leave her biological family and move in with her in-laws. But she does not just change physical residence. The culture governing the sasurāl-bahu model requires the bahu to place herself under the supreme authority of her mother-in-law, whose commands she must obey. She must accept her mother-in-law (sās) as her real mother from now on, and she must sever her links and affections for her biological mother.24This characterization of the sasurāl-bahu family structure is a generalization. Many bahus enjoy a loving relationship with their in-laws. Nor does every bahu move into the household of her in-laws. These exceptions to the rule are found in cosmopolitan cities like Mumbai and New Delhi. The sasurāl-bahu model is the norm in rural India, where the vast majority of the population lives. From personal experience living in a Khoja Ismaili community in Dar es Salaam, I would venture to remark that the grip of the model was weaker among them than it was among the Punjabi Ismaili Jamat in Punjab. This subject merits a comparative doctoral-level study.

Of all the adaptations that the bahu must make in her new family, the one that brings the bahu most directly under the authority and surveillance of the mother-in-law is the kitchen (and washing clothes). The bahu must carry out a range of household chores and duties that were carried out by the mother-in-law and her daughters—and even by the servants, among whom she is conceptually assimilated as the bahu-servant—before the bahu entered the family. In practice, then, the stranger who comes into the family as bahu becomes more a servant than a bona fide equal member of the family, enjoying the same love, care, consideration, honor, respect and indulgence as do the daughters of the in-law family. Hundreds of millions of bahus in Indian society are fated to a life of slavery, of trapped servitude inside the sasurāl-bahu social microcosm. The internet is full of young freshly married women, many mere teenagers, complaining about their mother-in-law and seeking practical advice on how to overcome their problems.

Under no circumstances must the bahu leave her in-laws and return to her birth family. She may have been mistreated by them, but she must put up with this abuse and, Sita-like, carry out her bahu duties silently and diligently. Indeed, she must not do anything to provoke them into abusing her even more. A bahu who flees her in-laws is an instant disgrace to her family's reputation, for she destroys the marriage prospects of her sisters.25One of my coworkers during my IT career was a Sikh from Chandigarh, capital of (Indian) Punjab. He went back to India to marry the girl he loved. While he was still in India, he sent us digital photos of the wedding ceremony. When he returned two weeks later, he was alone. He explained to me that his wife, the bahu, had to remain behind because she had to learn the family traditions from his mother. He and I shared the same cubicle, and our workstations were next to each other. About two weeks later, the phone on his desk rang. He spoke in Punjabi, which I cannot speak fluently but can understand. He was livid, shouting at the person at the other end. He was demanding that this person go back. Otherwise, he threatened, “I will divorce you.” He hung up, unable to calm down, his face exploding with anger. He turned to me and told me that his wife had called him from New York—New York!—and informed him that she could not take her mother-in-law’s abuse anymore, so she had fled the household in Chandigarh and had landed in New York on her way to be with him in Olympia (Washington) [I was living in Olympia at the time]. He took time off again from work and went back to Chandigarh. He swiftly divorced his wife and returned with a new bride. He told me in a firm voice, “I will not tolerate my wife complaining about my mother.”

Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah, ever so tremendously insightful, writing about the status of women in India in his book India in Transition (1918), made the following observation:

Generally speaking the Hindu joint-family system, as petrified by case-made law, operates to turn widows and married women into either domestic tyrants or slaves. [pp. 258-259; emphasis added by me]

In speaking of the "married woman," the Imam is referring not just to the bahu, but also to the sās (mother-in-law). It is typically a zero-sum game: if the mother-in-law is the tyrant, then the bahu is the slave, and if the bahu is the tyrant, then the mother-in-law is the slave. Which of these two alternatives is the outcome depends crucially on the son. A strong-willed bahu may succeed in "capturing" the son and, through his passivity, dominate and bully her mother-in-law—he is a weak son. Conversely, the mother-in-law may retain her hold over her son after his marriage and, again through his passivity, bully and mistreat her daughter-in-law—he is a weak husband. The weak son is weak in his relation to his mother but not weak in relation to his wife, whom he too may mistreat.

As Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah rightly observed, the joint-family system (sasurāl-bahu system) can turn the bahu into a tyrant or a slave. Indian films for decades have grounded their plots on the sasurāl-bahu family system and have made the relations between sās (mother-in-law) and bahu (daughter-in-law) the driver of plot development. It was Tajbibi's great misfortune that she married into a family in which the mother-in-law, aided and abetted no doubt by her relatives and by her own husband, became an all-powerful dominatrix over her and turned her into a slave.

Homology between the Caste System and the sasurāl-bahu Family System

The ubiquitous and deeply ingrained sasurāl-bahu family system and its structurally fostered domestic cultural system cannot be understood without also examining its place within the wider caste system in India. The caste system is the hierarchically ordered social embodiment of a theory of inequality-at-birth. Humans are born unequal, and their place, privileges and duties in society must be commensurate with this "birthright" inequality. This principle of inequality, which governs the caste system, imbues the individual with an inegalitarian outlook toward fellow humans—one is either above others or below them, but not equal to them. Even members of an upper caste constantly jostle to establish a hierarchical, inequality-based, relationship among themselves.26The most incisive and, as yet, unsurpassed study of the principle of inequality-at-birth and its social expression in the caste system is that of Louis Dumont, Homo Hierarchicus: The Caste System and its Implications (1966). Dumont subsequently published a second edition of the book (1980) in which he responded to the discussions within the academic community prompted by his provocative and controversial thesis.

The sasurāl-bahu family structure, which proved so oppressive to my mother, is, from a straightforward sociological consideration, a microcosm of the all-pervasive caste system in Indian society. It may have only two "castes" in it—the sasurāl (in-laws) and the bahu (daughter-in-law)—but it reproduces in this microcosm the fundamental value system that undergirds the wider "macrocosmic" caste system in Indian society. The key principle that engenders this homology between the family and the societal caste system is the role that the in-laws impose upon the bahu: they demand from her that she perform tasks for them that are performed by the sudra caste in the wider society. Whereas in the external wider caste system there are the three dominant castes—Brahmins (priests), kshtrayas (warriors) and vaisyas (merchants)—these three formal categories are fused into one de facto "upper caste" category, the sasurāl. The bahu becomes a one-person sudra caste laboring like a "slave" (as Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah put it) for the comfort of her in-laws.

There is a second principle that corroborates my homology between the family as a microcosmic caste system and the wider "macrocosmic" caste of Indian society at large: members of the upper caste do not think that they ever behave badly toward the sudra caste. The concept of guilt is foreign to them. They only respond to shame. The former is an individual's sensitivity and responsiveness to his or her own conscience. The latter is an individual's sensitivity to others' opinion about him, to his image among them, to his standing among them, all of which he wants to protect. In guilt, one punishes oneself. In shame, one fears retribution from society that has been offended by his conduct, and it is this fear of offense taken by society that evokes the feeling of shame in him. Guilt is directed inward, shame is directed outward. In guilt, moral accountability is directed inward, to the judgment of one's conscience; in shame, moral accountability is directed outward, to the judgment of others.27Salman Rushdie fails to distinguish between guilt and shame in his highly acclaimed 1983 novel, Shame.

No matter how atrocious, cruel and injurious the actions of the upper caste toward the slaving and powerless sudra caste, the notion of a conscience-stricken guilt is foreign to them. It is out of the question for them to feel remorse and guilt and to apologize to their victims for the emotional, physical and financial harm they have inflicted on the sudras. Indian films constantly depict these realities in their stories.

Both these key factors in the microcosmic sasurāl-bahu caste system were active and played a decisive and damaging role in my mother's life. For example, none of them—those who have passed on and those who are still alive—has ever expressed remorse, regret, or apology for their treatment of her, nor has any of them expressed any gratitude or appreciation for all that she did for them. This behavior is fully consistent with the ethical logic of macroscopic inter-caste relations, a logic that is reproduced in the microcosmic sasurāl-bahu caste system. [It bears repeating here that it was my mother's wedding jewelry and her salary from teaching that brought them to Africa and that nourished and sustained them even as they abused her.]

The contrasts between the respective mothers—her husband's mother and her own mother—could not have been starker and could not have failed to register with Tajbibi. One mother (Tajbibi's) was a compassionate if easily bullied woman who adopted orphans without regard to whether she would have the wherewithal to care for them. The other mother (Tajbibi's mother-in-law) rejected Tajbibi as a bona fide full member of her family and, catastrophically for Tajbibi, confined her to the toilets used by the servants. Her mother-in-law was, and remained till the end, ungrateful and cold-hearted toward Tajbibi and drove her like a slave master drives his slave. Yet she would not have been free to mete out her cruel actions on Tajbibi had the rest of the Aziz family, including, I am sad to say, her own husband—who cut a Ram-like figure, putting his loyalty to his family and family norms ahead of his obligations to his vulnerable, defenseless and bewildered young wife—stepped in to protect her.

The Animus Toward the Khoja

Contributing and reinforcing her in-laws' attitude and conduct toward Tajbibi was the animus toward the Khoja that they harbored. Whether this animus was a general feature of the Punjabi Ismaili Jamat or not remains an unanswered question for me. But I can say with the certainty of someone who has heard such sentiments expressed by some of them—khoje log zaeef hain ("the Khoja are a weak people")—is that it was a firmly held view within Tajbibi's in-law family. This superiority complex to their Khoja brethren—an unedifying aspect of intra-Ismaili relations within the Indian Jamats—hardened the in-laws' dislike for Tajbibi and exacerbated their mistreatment of her. [Yet, in a great irony, all Tajbibi's brothers-in-law and sister-in-law ended up marrying Khoja partners. Well they might: the Khoja Jamat in Africa was a flourishing Jamat. Marrying into them was to marry up economically.]

The Beginnings of Abuse in Africa

I have already recounted the monstrous "toilet" humiliation that my mother suffered at her in-laws' home in Amritsar; and I have also remarked that Tajbibi regarded her transfer to Africa (as per Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah's instructions to her husband) as her opportunity to escape from the clutches of her in-laws. She was sorely mistaken in this belief.

Tajbibi and Alwaez Abualy (along with me, a six-month child) left India before Partition tore asunder the Muslims and Hindus. At Partition, some of Alwaez Abualy's family fled south to Mumbai, where they were welcomed and hosted by Tajbibi's parents and brothers. Others, especially the daughters, were already living in areas that would fall on the Pakistan side of the border. Alwaez Abualy's younger brother had moved to Mumbai to avoid the blood bath. [Alwaez Abualy told me on several occasions that Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah had advised the Punjab Jamat living in what would become the Indian part of post-Partition India—for example, Amritsar—not to go to Pakistan but to go to Africa. The move to Mumbai was a step toward migration to Africa.]

Soon after Partition, Alwaez Abualy brought his younger brother to Dar es Salaam to stay with him and Tajbibi. This younger brother, Tajbibi's eldest brother-in-law, had exhibited the strongest animus toward his new Khoja sister-in-law. Now here he was, in her home in Dar es Salaam. But the "power logic" of the sasurāl-bahu model is a cultural characteristic: it is invariant with respect to physical location. Her brother-in-law may now be living in her home, but he was the sasurāl man, and as such he still retained the culturally sanctioned right to be her lord.

Although the Aziz family (Tajbibi's in-laws) was given to a higher than average level of temper, Tajbibi's brother-in-law exceeded them with his vile temper that he directed toward his powerless and weak sister-in-law. He was a bully pure and simple, striking fear into Tajbibi's heart and crushing her spirit. Alwaez Abualy had brought his younger brother to live with him to ensure that there was a male figure at home as he embarked on his Waez tours that took him as far as the Congo and South Africa. The younger brother thus found himself alone with Tajbibi and could wantonly dump his vile temper on his helpless sister-in-law who cooked for him, washed his bed sheets and took care of his other chores like washing, ironing his clothes and preparing the hot water for his bath.

A feature of the sasurāl-bahu model of the family is that it grants the husband's male siblings the right to "discipline" the bahu, striking her if necessary.28During the mid-70s in Cambridge (Massachusetts), when I was a graduate student at Harvard, a young Ismaili couple from Pakistan arrived in Cambridge. The wife had Bollywood good looks and flowing black hair; she always wore an elegant sari. The husband had joined MIT’s MBA program at the Sloane School of Management. His younger brother was living with them. It did not take long for some of us—we were a small student Jamat of about 15, gathering at MIT once a week for prayer services—to learn that the younger brother was beating his sister-in-law. When the wife finally opened up to us, she told us that her husband supported his younger brother’s actions, saying that he had the right to beat her. She had no marketable skills, was already the mother of a young girl, and had grown up in Pakistani society with traditional conceptions about stay-at-home mothers. In spite of these constraints, she eventually divorced the husband and became brave enough to live alone (with her young daughter) in the greater Boston area. I and a group of Ismaili students would visit her on weekends during the summer breaks and spend a few afternoon hours at her home playing Monopoly. Tajbibi's brother-in-law never lifted his hand to strike her, but he did view himself authorized by the norms of his own family to act as the "stand in" husband-lord in the absence of his brother.

This was the pattern of life for Tajbibi during the years 1948 and 1953 (when the other Aziz family members joined the Abualy household). Alwaez Abualy was gone on his Waez tours believing that he was leaving his wife in the safe care of his younger brother. The Abualy home was tucked deep into what local parlance would call the "jungle," cut off from the city and from the Jamat. It was not just a fearful place at night, it was also a prison from which Tajbibi had no escape from the harsh manner in which her brother-in-law treated her.

The only relief she found lay with the Waezeen students who showered her with love and respect. Although the majority of them lived in the city and returned home after classes, there were a few "foreigners" from the interior Jamats who lived in the dormitory component of the Ismailia Mission Centre building, a bungalow about half a mile from our home. One special student was the black indigenous Jaffer Sadiq. Alwaez Abualy occasionally asked him to stay with Tajbibi and her brother-in-law during his absences. Jaffer Sadiq was a very sensitive, caring and humane young man, and he treated Tajbibi with the kind of brotherly love and respect that he showed to his own sisters. These Waezeen students, especially Jaffer Sadiq, did a lot to soften the pain of her brother-in-law's vile temper and bullying.

The In-Laws Join the Abualy Household in Dar es Salaam

In 1953 Alwaez Abualy decided to bring his immediate family to Dar es Salaam. All together five new members from the Aziz family were added to the Abualy household.

An obstacle to bringing them over was lack of adequate funds. Alwaez Abualy was a very frank speaker not given to diplomatic niceties or concern over ruffling leadership feathers. His Waezes occasionally provoked strong reaction from sections of the Jamat and the leadership. This would happen when he said something controversial. Invariably the leaders responded by suspending his pay, which caused great hardship to my mother who had three very young sons and her brother-in-law to feed, not to mention feed her own husband and herself. The family could not pay the school tuition fees, as a result of which we would be sent home. Although her brother-in-law worked at a store in the city, he did not share any of his salary with Tajbibi. To add to the woes regarding school, Tajbibi did not have sufficient funds to pay for our school uniforms or buy shoes. I remember going to school without shoes. Mercifully, some fellow teachers of Tajbibi would donate their children's hand-me-down clothes to her for us to wear to school.

Alwaez Abualy may have decided to bring his family over to live with him, but he could not on his own cover the expenses involved. In order to meet the expenses of bringing them over, Tajbibi, Sita-like, sold some of her wedding jewelry and gave the money to her husband.

No sooner were they settled than they began treating Tajbibi as a slave who had to be at their beck and call all the time. Every individual among the in-laws, including Alwaez Abualy's youngest sister who was barely twelve at the time and was 15 years younger than Tajbibi, showed contempt for her and used harsh language toward her. She had to cook for them, do all the chores of the household, care for and feed her own children and the boarders, and teach at the Aga Khan Girls' Primary School.

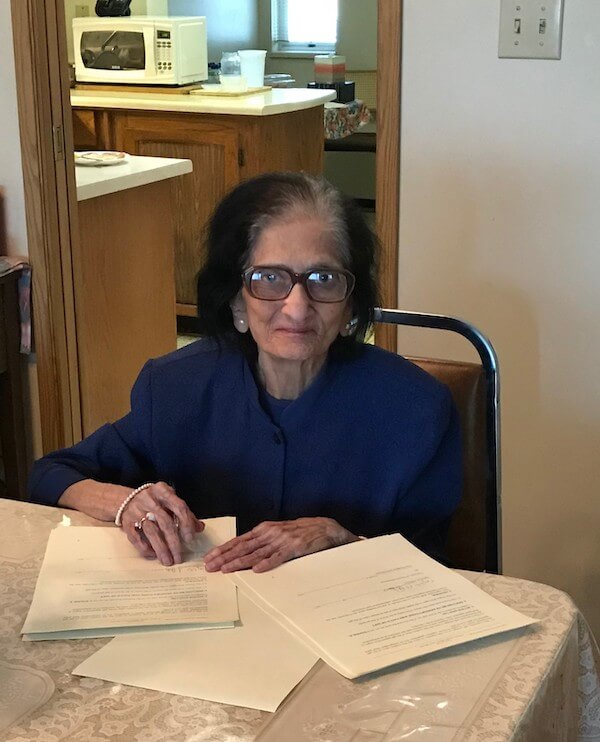

(More out of financial desperation than for any other reason, Alwaez Abualy started hosting young girls and boys from the interior, where parents were keen to send their children to the city to obtain education that was unavailable in their small town or village. These boarders, especially the girls, needed much sensitive emotional care in addition to good nutrition, etc. The parents had to be reassured that their children were being treated well. These tasks fell on Tajbibi's shoulders, which she, again Sita-like, discharged with compassion and diligent care.)